Michel Poiccard is in Marseille, he refuses to stay with a girl because he intends to go to Italy. He steals a car and, due to improper overtaking, two police motorcyclists follow him. Kill one of them and flee to Paris. There he wanders trying to collect a debt. First he takes money from another girl and then seeks the company of Patricia, an American student who sells newspapers on the street. Michel doesn't quite know what to do: he periodically calls his debtors, spends time at Patricia's house, accompanies her to the airport to interview a fashion writer, commits petty thefts to get by and gets another car… Meanwhile, the press reports that he has been identified as the motorist's murderer and the police are closing in on him. Patricia ends up ratting him out and letting him know that they are going to look for him. Michel doesn't seem to care, although he tries to flee; but he ends up being shot down by some agents and dies in the middle of the asphalt, but not before joking with Patricia.

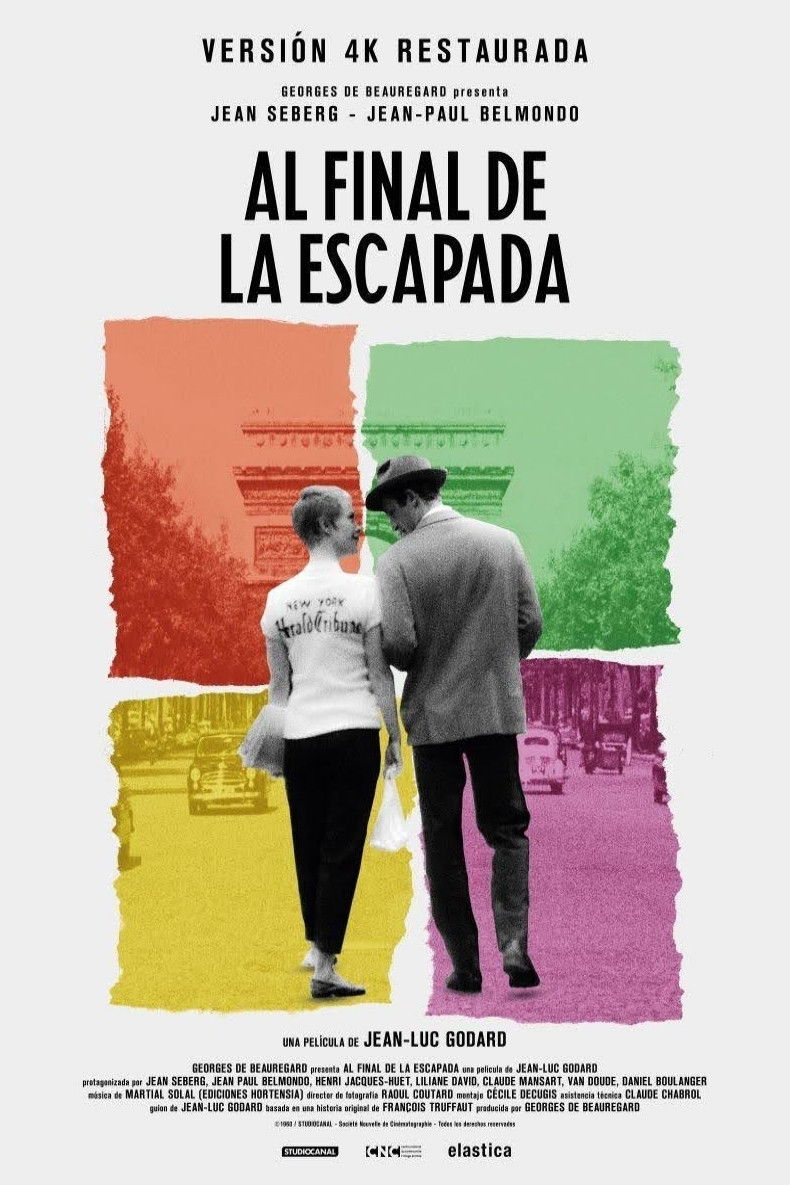

In At the end of the getaway, Godard, in his first feature film, is supported by some names of the new wave: the script is by François Truffaut, the photography by Raoul Coutard and Claude Chabrol appears as technical advisor; even the filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville plays the character of the writer Parvulescu. There are numerous cinephile references – for example, a young woman approaches Michel to sell him the magazine Cinema Notebooks– and the film itself is a tribute to American gangster films, although from a refreshing perspective. The North American reference is present in the dedication to the Monogram, the gestures of Bogart putting his fingers to his lips that Michel repeats, jazz music, the newspaper New York Herald Tribunethe movie The harder the fall will be (The Harder They Fall, Mark Robson, 1956), American cars, etc.

Godard explains his intentions: “What I wanted was to take a conventional story and shoot it in a completely different way than it had been done before. I also wanted to give the feeling that cinematographic techniques had just been discovered.” Indeed, the police skeleton is an excuse for a story that contradicts many elements of the genre and classic cinema in general; filmed with the camera on the shoulder and with natural light in much of its footage, there are numerous elements of rupture: absence of causality and motivation of the actions, colloquial conversations where one jumps from one topic to another arbitrarily, axis jumps, editing of shots without observing the 30º rule, a character addressing the camera, transgressions of connectionsequence in untranslated English, proliferation of second-level images (photos, posters, mirrors), neons with texts announcing Michel's arrest, single-shot sequences, rejection of the shot/reverse shot, etc. There are also some of the themes of the new cinemas such as the aforementioned cinephilia, the references to books and novelists (Faulkner), the cultural topics of the time (interview with the writer at the airport), the life cycle of a young man, the fatality of existence and the resolution of the conflict, sexual disinhibition and statements that summarize the theme such as “Living dangerously until the end”, “Between grief and nothingness I choose nothingness, because grief is a commitment” or “I “I'm going to die. I'm tired.”

The result is a choppy, open story that questions the viewer about the background of the pose that the protagonist adopts at all times. Michel is an idealist hero, an anti-system fighter who embodies the vital attitudes of rebellion with nihilistic traits very typical of existentialism. His arrogance with women – and with the rest of the people – and his desire for sexual relations without commitments contrast with Patricia's weakness before him, despite the fact that she has greater convictions about life. The continuous time of the story and the police plot contrast with the long conversations that the two protagonists have in Patricia's apartment and which reveal Godard's basic interest in investigating personalities, even beneath dialogues that mix issues, show silences, abound in clichés and barely outline the deep motivations. In short, as Esteve Riambau summarizes, «Heir to existentialism and contributor to the passion for North American cinema, At the end of the getaway It emerged at the end of the fifties with the force of an unavoidable avant-garde work. The absolute freedom of movement of a camera moved on a wheelchair or a mail cart, the use of sensitive film that allowed filming with natural light and, above all, a conception of editing that created a new definition of cinematographic space and time, approximate the first work from Godard to the rupture of classical narration.

Source: https://cineenserio.com/al-final-de-la-escapada-a-bout-de-souffle-jean-luc-godard-1959/