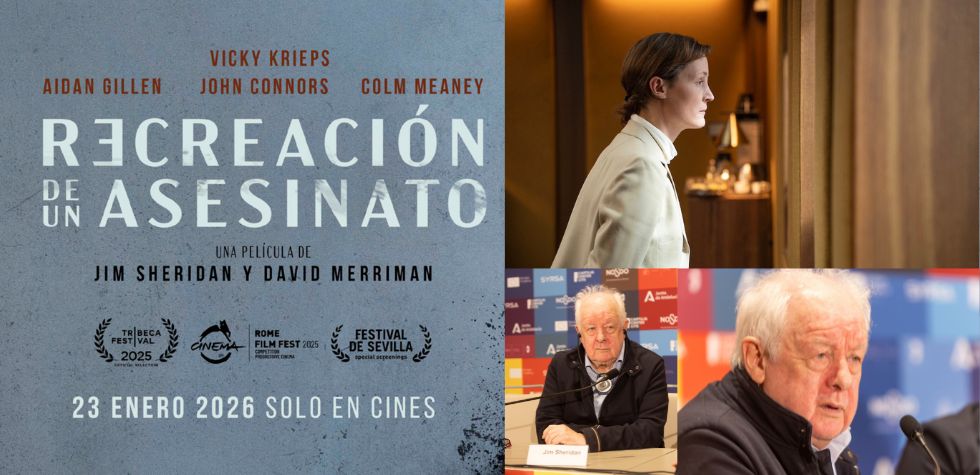

At the latest edition of the Seville European Film Festival, Jim Sheridan received the Giraldillo of Honor in recognition of his career and his deeply human outlook on social and political conflicts in the world in general, and Ireland in particular. During the contest, he presented his latest work, Murder reenactmentco-directed with David Merriman, a bold mix of fiction and docudrama that imagines the trial that never took place in the real case of Ian Bailey and the murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier. The film will be released in Spain on January 23, 2026, offering a reflection on justice, truth and the uncertainties surrounding one of the most high-profile crimes in recent history. We spoke to the Irish director about his political beliefs, his trip to Hollywood and the new names in Irish cinema.

Murder reenactment reimagines the Ian Bailey case as a jury trial that never actually took place. What led you to this very particular approach of mixing documentary elements with a fictional reconstruction, and how did you handle the ethical complexities of dramatizing a real and still open legal matter?

I think it's probably the first time a real case has been recreated in a jury room that never existed. I don't remember another situation in which recreated truly a real martyr. Sidney Lumet made a great movie, Twelve men without mercywhich is brilliant and fascinating, surely his best work, very controlled, with an incredible performance by Henry Fonda. And the most I could do was get closer to that image. But the advantage of working with a real person was that the audience knew perfectly well who the accused was, and that did not happen in Lumet's film, where you only see the accused for a moment and he is more of an abstraction.

That gave me an advantage, but also a disadvantage, because I didn't have the time that Lumet had, who was also a genius with the camera. There was a trial in France where Ian Bailey was found guilty, but he was never tried in Ireland, and that raises a lot of questions about European jurisdiction: if we are in a situation where the French don't allow us to interview people in France, they try an Englishman living in Ireland, declare him guilty and expect him to go voluntarily, are we crazy or what? What is Europe then? The British left Europe with Brexit, in my opinion a disastrous decision, partly due to legal issues: they questioned who controls the European Court, what system is applied, if we continue to apply a napoleonic law o one common law… In Ireland the so-called common law inherited from the British, which has many problems, just like the napoleonic law. But I don't like the idea at all that they can refuse to let the Irish police go there and talk to people in France. It seems very bad to me, and I would like a few questions answered.

We have reached a point where we can no longer believe what we see. An image is worthless.

Jim Sheridan, director of Murder Reenactment

The film addresses themes of justice, prejudice, and reasonable doubt to reflect the modern complexities of not only this case, but society today. There is also talk of fake news and how a group of people can see reality in different ways based on the same facts. What worries you most about all this?

Las fake news, From what I see, they are some kind of invention of the extreme right. The expression is intended to say that the news fake They are in the liberal press. When people hear the word newsI think he still thinks about paper, about what is printed, but now we have reached a point where we can no longer believe what we see. It used to be said that a picture was worth a thousand words; Now that image is worthless. There was a huge change when we went from celluloid to digital. Before you had 24 frames per second, the frames passed through the lens and the projector filled a good part of the screen, and although we knew that what we saw was fiction, we believed that it had happened really within the logic of the film. With digital, physical support was renounced and replaced by pixels, which form a frameless surface that can be manipulated. At first the changes were mainly in color or tone, but when cinema became completely digital, absolutely everything could be modified, and at that moment the viewer stops considering whether or not to believe what they see: they know that it is not believable, that Spider-Man does not fly, that Superman does not fly.

When the audience enters into that logic, what they want to see is the incredible, and belief disappears from the cinema to be replaced by the implausible. The problem is that it contaminates everything. We have reached a situation where political events, such as the assault on the Capitol on January 6, of which there are images, continue to be questioned and there are still people trying to convince us that it is something that did not happen. We live in a world of post-truth and it's not at all clear how to regain trust or how to know what you're looking at. That's why I'm so obsessed with the truth and with a kind of documentary reality: there are more facts than ever, but also more doubts. That, in turn, reveals something that cinema has almost never really thought about, which is the question of belief. We have to forget about classical narrative, mythology, the three-act structure or Joseph Campbell and The hero with a thousand faces; That's all fine as a way of thinking about certain types of movies, but it doesn't get to the place where people have lived for thousands of years, which is belief. They lived in belief: projected religious beliefs, like Catholics believe one thing, Protestants another, Muslims another, and Jews another. They are different belief systems, and in that sense a film is a belief system projected on the screen.

The cast embodies a jury deliberation with a very strong dramatic weight, and you yourself play the president of that jury. Why did you decide to physically appear in the film and how was your work with the actors?

I felt like I had to risk my neck. It was a project that I really didn't want to make a mistake on, because I knew there were going to be a lot of questions asked: if it was fact, if it was fiction, if it was a recreation. Think about the idea of reenactment: imagine that I am now reenacting our interview and that, at the end of the conversation, you murder me. To reconstruct that I would have to put the camera behind your back and make sure I don't see your face, because if I see it I'm saying that you committed the murder.

For a long time, recreations and documentaries have been almost contradictory: images that look like visual evidence, but that you can't completely trust, because they tell you two things at once: that it is a recreation of something true, but at the same time it is not true. I wanted to make a truer recreation, closer to a real reconstruction in which the faces could be seen. That involved putting real people in there, interrogating the facts with them and showing how each one analyzes those same facts from their own belief system.

He has traveled from his first films in Ireland to Hollywood trying to make a different type of cinema. What was the struggle like to go from that more social cinema in Ireland to a more gender-oriented cinema in Hollywood?

Hollywood, what a place! (Laughs) I think I've been asked that question before and I've probably tried to avoid it, but I'm going to answer it: the difficult truth was that I had run out of time in Ireland, that I had already made the films I could make there. So the opportunity arose to direct big-name actors, I became well-known and could earn more money in America. So yeah, I admit it, I took the money once or twice. And I think that, on some level, affected the way people perceived me. I don't know if it was a crime exactly, but it did break the belief system that exists in Europe a little. I think my Irish films are more like X-rays, while the American ones became a little more like simulations. Until I realized that I couldn't… No matter how much I tried to go as far as I could physically and mentally, I couldn't get as close in the American films as I did in my Irish films. I hope my answer makes sense (Laughs).

My Irish films are more like X-rays, while the American ones became a little more like simulations.

Jim Sheridan, director of Murder Reenactment

Are you in contact with movies like The Quiet Girl (Colm Barréad, 2022) y Kneecap (Rich Peppiatt, 2024) of young filmmakers who represent this new Irish cinema?

Yes of course. When they nominated The Quiet Girl For the Oscar for best foreign language film, I went to Hollywood to support the director, and I loved that it was in Irish and that it was such a big success. Just like Kneecapwhich is also in Gaelic. In fact, when the members of Kneecap were tried in London, I went to the trial to support them. So it's not just that I know them, but that I actively support them and do everything I can for them.

This morning I had the unfortunate honor to listen to a young man talking about Get Rich or Die Tryinga movie I made with 50 Cent, the first one I made just for the money. And he told me it's the best rap movie ever made. I asked him: “Do you prefer it to the Eminem movie?” And what about Straight Outta Compton“He told me that he also preferred her to that one. But he also told me that it is not as good as Kneecap. No matter how much I have done Get Rich or Die Tryingdefinitely does not have the strength and charisma of Kneecap. (Laughs). So I think that Kneecap It's a very interesting film, and they are very interesting people. The Irish take everything to heart and go with their hearts in their mouths. Nowadays I feel like something is exploding from the culture where some young people are saying “fuck you” to the system. I love them, I really love them.

Murder reenactment (Jim Sheridan & David Merriman, 2025)

Source: https://cineenserio.com/entrevista-jim-sheridan/