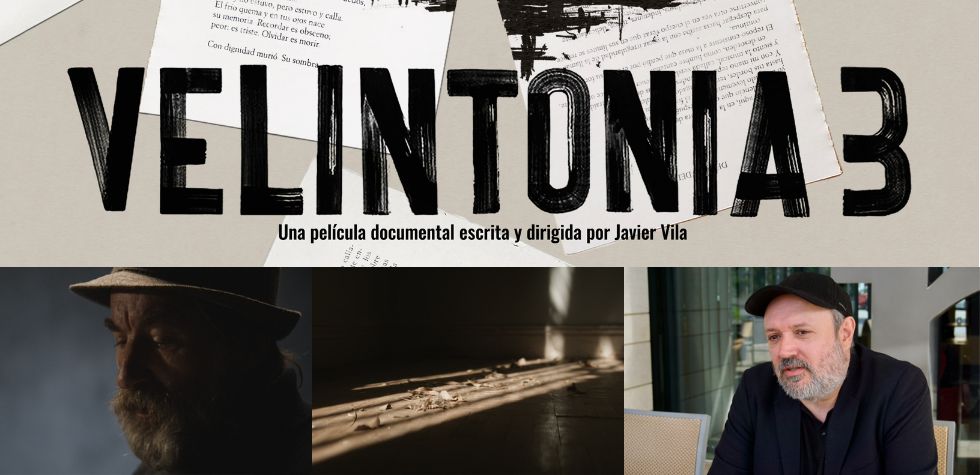

Velintonia 3 It is more than a documentary: it is an archeology of Spanish literary memory that hits theaters on November 28. After four decades of silence, the emblematic Madrid house of Nobel Prize winner Vicente Aleixandre reopens its doors through the cinematographic gaze of Javier Vila to reveal the layers of history, poetry and resistance that its walls kept during the 20th century. By combining testimonies from poets who lived through that era such as Vicente Molina Foix and Jaime Siles, narrations from Andalusian actors such as Antonio de la Torre and Ana Fernández, and a very particular sound architecture, Vila's documentary not only settles for a mere nostalgic reconstruction but turns Aleixandre's house into a living instrument. We spoke with Javier Vila about the challenges of filming absence, the ethical responsibility of telling stories of repression and freedom, and how a house can be much more than brick and lime and become a living monument to the dignity of art.

What was the exact moment that led you to decide to make a documentary about Velintonia and the figure of Vicente Aleixandre?

It all arose from a song by the group Maga, called The House of Number 3, the only song that has been written about the house, about Velintonia. They went to perform it in the house itself and, from there, the story came to us, because we know the people in the group. We made a visit to the house, a visit very similar to the one reflected in the film. I have always really liked empty spaces and all that magic that exists around them, but I found the state of the house in, the absolute abandonment, incredible to me. It had been closed for about 40 years, empty, with humidity, with pieces of fallen ceiling, chips, the marks of the bed where Aleixandre wrote all his work, all those traces that were left there. I found them super interesting.

I was also very impressed by the story of Aleixandre, one of the greats of universal literature, a Nobel Prize winner, and yet a great unknown; I include myself among those who know very little about him. Imagine a Lorca or a Miguel Hernández who had lived to be 86 years old, going through the entire history of Spain. That link between Aleixandre and the house, that house converted into a kind of temple of 20th century poetry through which an entire generation passed, it seemed incredible to me that it had not been told.

That concept of friendship was one of the great lifesavers of Aleixandre's life, building an entire ritual of visits and schedules so that the world came to him in an organized way.

Javier Vila, director of Velintonia 3

Plus, there was all the cinematic potential of abandonment itself and of those images. Aleixandre had a chronic illness since he was young that led him to lead a very inward, almost Zen-like life, and it seemed very suggestive to me to build a character based on all those traces of the house and, at the same time, offer an almost claustrophobic visual point of view, like that of someone who is always inside the house, who knows the nooks and crannies and the small ray of light that enters at a precise time. We were also very interested in sound, because it is fundamental. In fact, the soundtrack has been created from all the sound material that we were recording in the house: the creaks of the floor, the smallest details, that feeling of confinement of someone who always lives there. All that mixing was, in fact, what led us to embark on the project.

There is a moment in the documentary in which Vicente Aleixandre himself, in one of the recorded statements, says that the Generation of '27, more than a group of poets, was a group of writers that was also a group of friends. I like that concept that underpins the entire documentary: friendship, in a broad sense, friendship even despite the friction that existed between them. Velintonia was a meeting place for friends: did you have that in mind from the beginning or did it emerge as you went along?

It was emerging, but what you say is true: as soon as you pull the thread a little, you realize that, throughout all the generations, everyone agrees on this. Everyone was attracted to him because he was a very special person; He was extroverted, very endearing, and all the testimonies agree on that. For him, friendship was one of his great leitmotifs, along with love, of which he is also considered a poet, but he said that friendship was the purest form of love because you don't expect anything in return and, for that reason, it had such importance in his life.

I think that, in addition to his character, which already attracted people, he was dealt some complicated cards with the illness and the type of life he led, and friendship also served as support. He was nourished by the life experience of those who came to his house, it was as if the universe came to him, and he used all that as a human and also creative experience. From the stories they told him, he later ended up creating many of his poetic images. So yes, this concept of friendship was one of the great lifesavers of his life, taking that handicap into account. He barely left the house, but he had a lot of time to rest and had created a whole ritual of visits and schedules so that the world came to him in an organized way. I think it was one of the great ways he found to adapt to the world.

Another aspect of the documentary that I find very interesting is the vindication of some female figures, such as Carmen Conde and that Academy of Witches that is talked about. That idea of resistance and empowerment that, with the arrival of Francoism, was clearly relegated. What was it like to incorporate that feminine part that has been so often forgotten by that generation?

Well, with all the naturalness in the world, because it is something that happened in a very organic way. On the ground floor there was that whole atmosphere of poetry and creation around Aleixandre, and upstairs, on the upper floor of Velintonia, lived Amanda Junquera and Carmen Conde, who were a couple, and that other atmosphere was also generated there, that kind of spirit of Velintonia in a feminine key. It was not something highly sought after or planned for the documentary, but rather something that arose spontaneously from what was happening in the house.

On that upper floor, at number 5, was the so-called Witches Academy, and many stories were created there. Carmen Conde also had an agenda in which she wrote everything down, she was almost a documentation maniac, and that notebook is very interesting because it allows you to build a story from everyday episodes and the most human side of people. In those notes they talk about very natural things about Aleixandre: what he was like, what he wasn't like, what poem he wrote for that reason. There is very rich material there that would have even deserved to be studied even more in depth.

In the documentary you also have two generations of poets and writers: Vicente Molina-Foix, Guillermo Carnero, Jaime Siles, and other younger poets such as Raquel Lanseros or Juan Gallego Benot. Did you think it was important to show that link between those two generations?

Yes, because it is a reflection of what Velintonia 3 was like. The house was a meeting place and Aleixandre functioned as a kind of connector of generations, what today would be called a network of networkingbecause it brought into contact the young poets of the moment, who are now our octogenarian protagonists. They went there when they were 18 or 20 years old and Aleixandre related them to each other: he told them who to read, who to meet, and thus that plot was woven between different literary promotions that they themselves tell in the film.

In the documentary, sound and music function as a way to bring back everything that happened there.

Javier Vila, director of Velintonia 3.

For these young people it was shocking: they arrived at 18 years old and, suddenly, they found themselves in the house of an established poet where many people from the world of culture passed by. Showing this network served to reflect that connection and that point of union between all generations. For me, in addition to telling the viewer everything that happened there, it was important that when watching the film they felt that choral energy. There are, on the one hand, the living memories of those young people who now remember their history and, on the other, all those who are no longer here: those of '27, Neruda, Miguel Hernández, those of '50, present through letters and texts.

We also wanted the new generation of poets who know the house today to be part of that story, just like the documentary team itself. From there also arises the most artistic part: a kind of ritual or ceremony in the garden, emulating the spirit of Velintonia, with Llorenç Barber and Montserrat Palacios in a bell rite, readings of poems by the young poets and a soundtrack that collects the noises of the house, composing that choral story that expresses the connection that Velintonia exudes.

Another decision you make in the documentary is to incorporate Andalusian actors, such as Antonio de la Torre, Manolo Solo, Mona Martínez and Ana Fernández to dramatize certain writings and letters. Why did you decide it was them?

In Andalusia there is a lot of talent; what am I going to say. And, furthermore, I was very interested that, within that choral vision, they were not so much “interpreting” as such, but rather being themselves: actors and actresses who simply read some texts. The idea was that it didn't sound very performed or very dramatized, but rather like a kind of inner voice that is activated when you read and listen to a text being read. And they seem to me, honestly, to be one of the best. We were lucky to have them even though they were all very busy filming: Manolo Solo with a series about 23F and another film, Ana Fernández in a daily series, all against the clock. Even so, they found a space and we were able to put their voices at the service of all those who are no longer here.

You have talked about the music and how the sound of that empty space that you mentioned before is fundamental in the documentary. As it is said in the film itself, the house functions almost like a living instrument. How did the idea of using the house also as an echo space come about?

For me it was a bit like being inside Aleixandre's head, that point of view of someone who is always at home. Just as with the image you take a tour of the small details—a passing spider, a crack, a light—the same thing happens with sound: I am interested in capturing the silences, the small noises, the creaks, and incorporating them into the soundtrack. Velintonia 3, in addition, was a very musical place: the Generation of '27 met there and Lorca played Aleixandre's mother's piano at many of those meetings. We also wanted to recover that kind of magic, with a very present piano, but treated with reverberations, like an echo that always sounds in the distance, as if the music could continue playing in the house.

The editing and pace of the film are slow, contemplative, very minimalist, and that is why it seemed important to me that the music was present almost all the time, not only in the form of piano pieces, but as an internal heartbeat, a cushion or soundscape that pulses continuously. Just as we bring back the stories told, the idea was that sound and music would also function as a way to bring back everything that happened there.

Velintonia, 3 (Javier Vila, 2025)

Source: https://cineenserio.com/velintonia-3-entrevista-javier-vila/