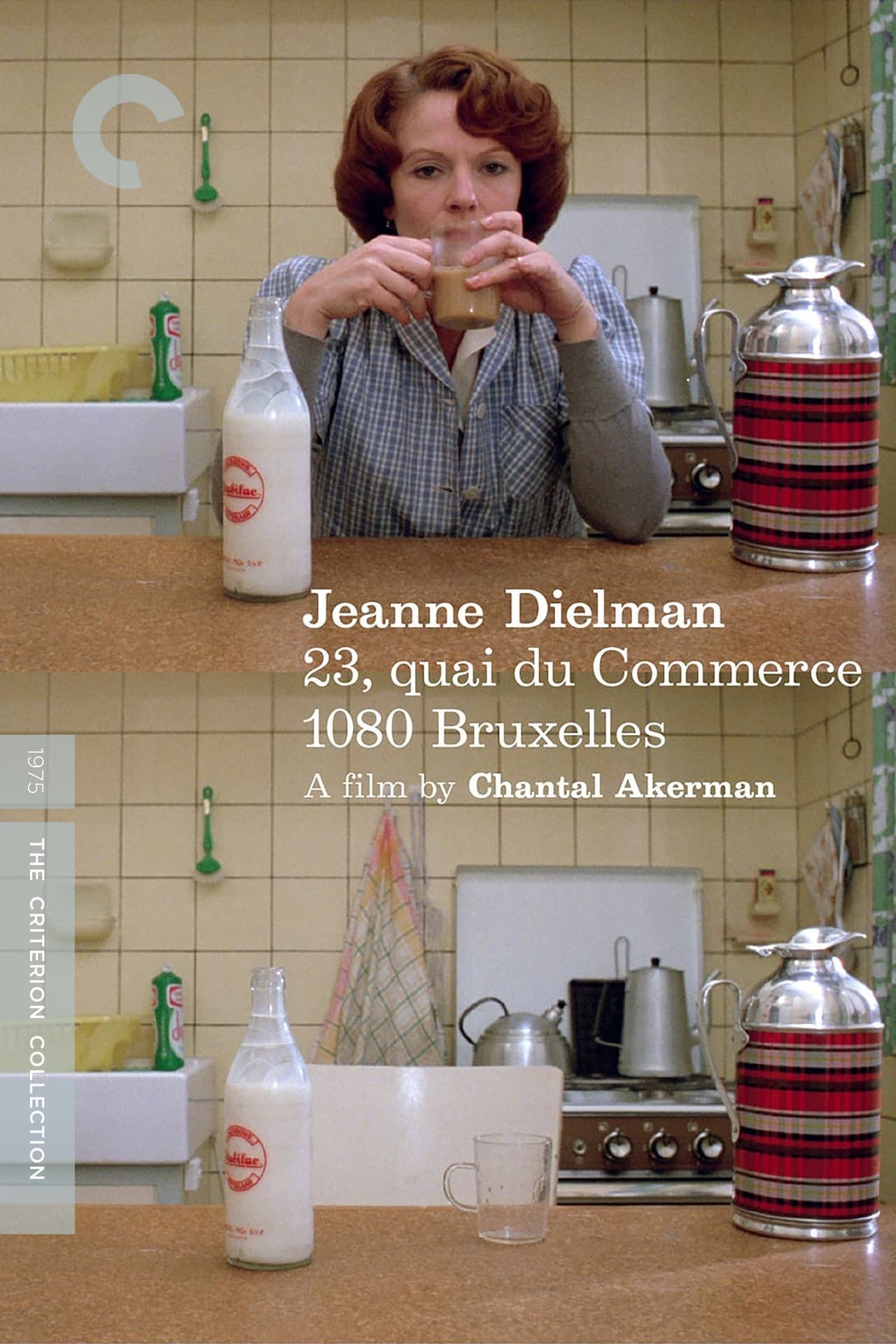

Social networks have been on fire at the beginning of November due to the publication of the Sight & Sound magazine, edited by the British Film Institute, of the hundred best films in history after voting by more than a thousand specialists and film critics. We live in a society where we really like to compare and develop this type of rankings and we should always take them with a grain of salt, since due to the great deal of objectivity when preparing these lists, it is evident that everyone’s taste is very personal. However, it is very noteworthy to note that Jeanne Dielmanthe groundbreaking and innovative proposal by the Belgian director Chantal Akerman back in 1975, has slipped in as the first on a list of such magnitude, in which filmmakers of the stature of Martin Scorsese or Aki Kaurismaki have voted. The world is advancing and with the entry of the new millennium it is increasingly common for talented women to have more tools and fewer impediments to access the seventh art, and it is evident that these social demands have also reached the world of cinema. For this reason, I think it is also fair to remember those filmmakers who paved the way for Claire Denis or Carla Simón, such as Ida Lupino, Kinuyo Tanaka, Maya Deren or the Belgian filmmaker herself that we will talk about below.

Jeanne Dielman is a minimalist masterpiece that It recounts the insufferable life of the protagonist without artifice, with a narrative tempo that, compared to it, any Antonioni film would seem like an incredible exercise in entertainment. That is precisely the objective of Chantal Akerman, to show the bleak and monotonous routine that this poor woman leads, resigned to being a housewife with no other ambition in life. Therefore, we find ourselves before a masterful feminist study on the existential emptiness of any housewife.

The film narrates the daily life of Jeanne, a young widow who lives in an apartment in Brussels with her teenage son. The film is built from the so-called “dead times”, showing a certain interest in filming everyday and anodyne scenes, consisting of all those domestic tasks that are normally overlooked when making modern films. Akerman uses in all his scenes fixed planes and frames that are out of field, with a camera that sits at a specific point in some of the rooms of the house, filming Jeanne’s real life full of banal tasks, all of them taking place in real time, which will make us fully immerse ourselves in that seventies flat where develops almost the entire film. Jeanne seems to behave like a woman who has been emptied of everything, and her obsession with repeating the same tasks every day seems to be a defense mechanism and a way of escaping from her sad existence after the death of her mother. husband of her She even acts like a robot when she practices prostitution in her house, always following the same guidelines and customs.

The cinema of this Belgian director is not suitable for all audiences. If in most films she shies away from narrative scenes that add nothing to the plot, Chantal Akerman does just the opposite, focusing on the mundane of daily life. The Belgian director’s contemplative gaze on her protagonist is reminiscent of the works of Eric Rohmer, but here with much more emphasis and without resorting to dramatic moments. As we reach the final stretch of the film, we will verify the destructive psychological evolution of this housewife, that when she loses order in her routine, she no longer has anything left, and thus we reach the surprising final climax.

In short, we are facing a heavy and soporific film, but whoever is looking for another type of cinema that is close to real life will be reciprocated with the magnificent film that Chantal Akerman gives us. Jeanne Dielman es a very human work, despite how icy it appears to the naked eye. It is never more to claim this cinema and remember that there were already women who many years ago were making history in the seventh art.

Source: https://www.cineenserio.com/jeanne-dielman-23-quai-du-commerce-1080-bruxelles-de-chantal-akerman/